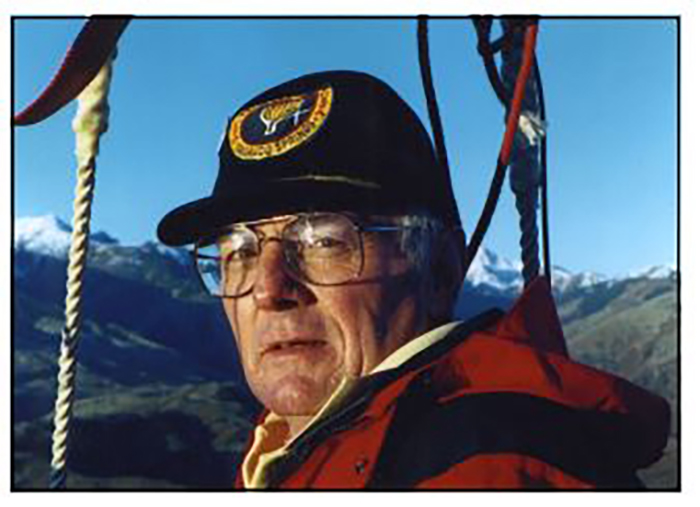

Dewey Reinhard had never seen a balloon as huge as the one that he was about to fly on October 10, 1977 from Bar Harbor, in the United States. Reinhard and former Army pilot Steve Stephenson were lured by the Atlantic as were others before them, whose quest had produced 15 failures and five deaths. But with three years of experience in flying hot-air balloons and two training flights in gas balloons, Reinhard was sure that he would achieve the dream of flying a balloon across the Atlantic Ocean, from United States to Europe.

Because balloons have no steering mechanism, the only way pilots find ways to their tentative destinations is by raising or lowering the whimsical aircraft to altitudes with favorable winds. In a traditional zero-pressure gas balloon, the envelope is filled with lighter-than-air helium gas (or hydrogen). To rise, balloonists throw ballast (heavy material taken for the purpose) and to descend, they valve out the helium from the balloon.

Now picture flying over the Atlantic Ocean in 1977, in an open gondola, with no supplemental oxygen, suspended under an 82-foot long balloon, filled with 86,000 cubic feet of helium! It was “The Impossible Dream,” as CBS television described it.

Before his trans-Atlantic attempt, Reinhard had two overnight training flights by Ed Yost in Amarillo, Texas, in Ed’s plastic gas balloons. “Ed told me that he had designed these balloons for years to deliver spies from the decks of submarines during the Cold War,” Reinhard said in an interview with LTA-Flight Magazine.

So, when Reinhard and copilot Stephenson took off in their balloon Eagle to fly across the Atlantic Ocean, it was Reinhard’s first independent gas balloon flight. The whole system and the balloon would cost Reinhard $200,000 and to raise that amount, Reinhard mortgaged his house. Fortunately, CBS television agreed to sponsor on condition that the flight would be broadcast on prime-time television a couple of times. “It was a lot of money,” said Reinhard who was certain that they would make it. “We were committed, and we had a lot of pretty sophisticated equipment on that balloon but some of that didn’t work.”

However, the balloon built by Ed Yost worked perfectly and the boat-like gondola built by Reinhard also worked perfectly. “Several other balloons, in the 15 attempts before ours had failed and cost people their lives, but Ed’s balloons—they never failed. That was why I chose Ed to build the envelope,” said Reinhard who put all avionics and other equipment in the balloon. “We tested the gondola to see if it would float and yes it did, which saved our lives.”

They maintained a low flying altitude and trailroped across the Bay of Fundy, and 16 hours later were headed toward Bermuda. They spent the second night just above the surface of the water. The following morning as the helium expanded with the warmth of the sun, they rose 5,000 feet above but within few hours were hit by the worst storm in Halifax in twenty-five years. Balloon and gondola were engulfed in torrential rain and they plunged into the sea. They cut the envelope away and were rescued 20 miles southeast of Halifax. They had flown 200 miles, and their 47-hour flight was filled with exciting and tense moments, which Reinhard recalled vividly.

“I bet the weatherman just made a wrong call on that one. We had waited almost a month in Bar Harbor for what we thought would be favorable weather to make it to Europe. Unfortunately, I don’t think he saw that storm that finally overtook us.”

The pilots were exhausted even before takeoff as they were up for 60 hours getting ready to fly. “My copilot, Steve, hallucinated a couple of times on the flight, so it was tense. We didn’t rest properly, and we didn’t eat properly,” said Reinhard.

And while they were set up to communicate with the ground crew at the world weather center in Washington, DC, the singleband radio failed, and they had to relay messages through airlines and ships. They talked with airplane pilots frequently to ask them about their position and to get weather updates, but timely information was hard to come by. At one point, the whole system jumped, and they heard a loud explosion. They thought the balloon had burst. But they were hit by a severe sonic boom from a Concorde jet from England. “We talked to the pilot of the Concorde and asked him if he could slow down or do anything because he said that we could get hit with it again on their way back. But the next time he radioed us and told us that he would be about 20 miles past us when that sonic boom hit us on the surface.”

Besides being too busy, the scenery was too interesting for them to catch any sleep as they did not want to miss anything. “It was so beautiful in the mornings. Before the balloon would heat up, it was just the sound of us scooting across the water like being in a sailboat; the flag was dragging in the water quite often, and, we had trail ropes in the water, and we would be talking to the ships on the radio.” They also spotted a 50-foot gray whale, only ten feet away from them, which Reinhard said was very exciting, “especially for guys from Colorado.”

Without any supplemental oxygen, Reinhard planned to fly at lower altitudes and also go down to the surface of the ocean to pick water ballast when the balloon cooled off. Theoretically, he says, one could fly indefinitely, this way. “But the storm interfered with that, plus the fatigue of hauling that water overboard; we hauled about 500 pounds of salt-water ballast and then we had to dump most of it, when fighting the bad storm that we were caught in.”

They were in heavy seas near Halifax and rescued by a Canadian Coast Guard ship. “We hit the ship really hard a few times, but the gondola never failed.” Using polyurethane foam as a filler, Reinhard had designed it such that the gondola would float even if it was full of water.

“And, if we had made it across, we would have actually made some money on that flight. But it was a very short flight because we were just kind of going all over the place when that storm overtook us,” said Reinhard.

They recovered half the money from CBS television because a film of their flight, “The Impossible Dream,” was broadcast, a few times, on prime-time television.

Reinhard’s inspiration to fly a balloon across the Atlantic, came from the book Small World. “It was about some people in England that tried to fly in a balloon from the Canary Islands across the Atlantic, from east to west. I’d read that before I was flying balloons, and I just couldn’t get it out of my mind. And, I just decided after Bob Sparks and a couple of other guys had tried it, and we would hear about their ill-fated attempts, while I was flying in a national hot air ballooning competition, in Iowa. And I came home from work one night and told my wife, ‘we’re going to build a balloon and try to fly across the Atlantic Ocean.’”

Despite the terrible storm that overtook them and the dangerous splashdown in the Atlantic, Reinhard, also a sailor and an airborne sonar operator on an anti-submarine helicopter, was not deterred. He started preparing for a second attempt with a slightly larger balloon, three pilots aboard, and with CBS as their sponsor, once again. But on August 17, 1978 all that changed, and they had to abandon the plan. His compatriots Ben Abruzzo, Maxie Anderson, and Larry Newman had successfully flown their balloon Double Eagle II across the Atlantic, from US to France. Although, it must be noted that it was the second attempt for Abruzzo and Anderson; their first one was the year before, when they barely survived the long flight and had to ditch their balloon Double Eagle, off the coast of Iceland.

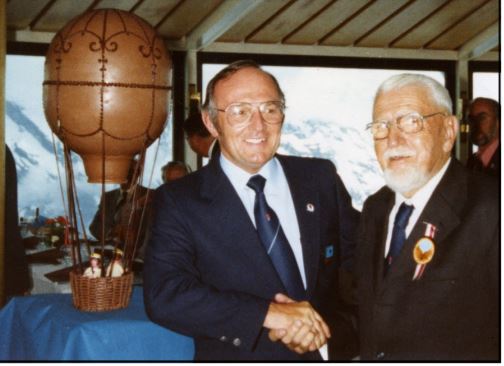

Though Reinhard could not achieve his dream of crossing the Atlantic by a balloon, he had several other adventurous flights and aeronautical feats that earned him many awards and honors. To name a few, he received the highest international award in ballooning “The Montgolfière Diplome,” he was inducted into the U.S. Ballooning Hall of Fame and the Colorado Aviation Hall of Fame, and also received Distinguished Aeronaut status from the Balloon Federation of America.

The noble failures and successes of the Atlantic attempts paved the way to improvements in technology and led to epic ballooning adventures, such as the transcontinental and around-the-world balloon flights. However, the attempts by these brave aeronauts to tackle the Atlantic in balloons with open gondolas and limited technology will always remain phenomenal achievements.

By Sitara Maruf

4 Responses

The article brought back many memories of our attempt, but I must correct one statement: I was not a fighter pilot, I was an airborne sonar operator on an anti-submarine helicopter.

Thank you, Mr. Reinhard. I enjoyed interviewing you and writing your inspiring story. Sorry about the error; I have corrected it.

I remember meeting with Dewey before his departure from Colorado Springs. I knew him as a cadet at the Air Force Academy hot air ballooning club. I was able to get his several cases of K rations and C rations for his trip. As I was originally from Maine we discussed his departure from my home state.

Once again, congrats on your attempt and ballooning enthusiasm.

Are Dewey and Steve still alive now in 2022